BEWARE! A Job Too Good to Be True: How Scammers Exploited the FAO Brand to Prey on Nigerian Job Seekers

BY: Mustapha Lawal

Job scams are a growing problem, with 25% of people reporting they’ve been scammed and 45% finding it challenging to avoid them. In 2023, the Identity Theft Resource Centre (IRTC) reported a 118% increase in job scams. Scammers often lure job seekers with enticing offers and then demand upfront fees or trick them into sharing personal information.

Introduction

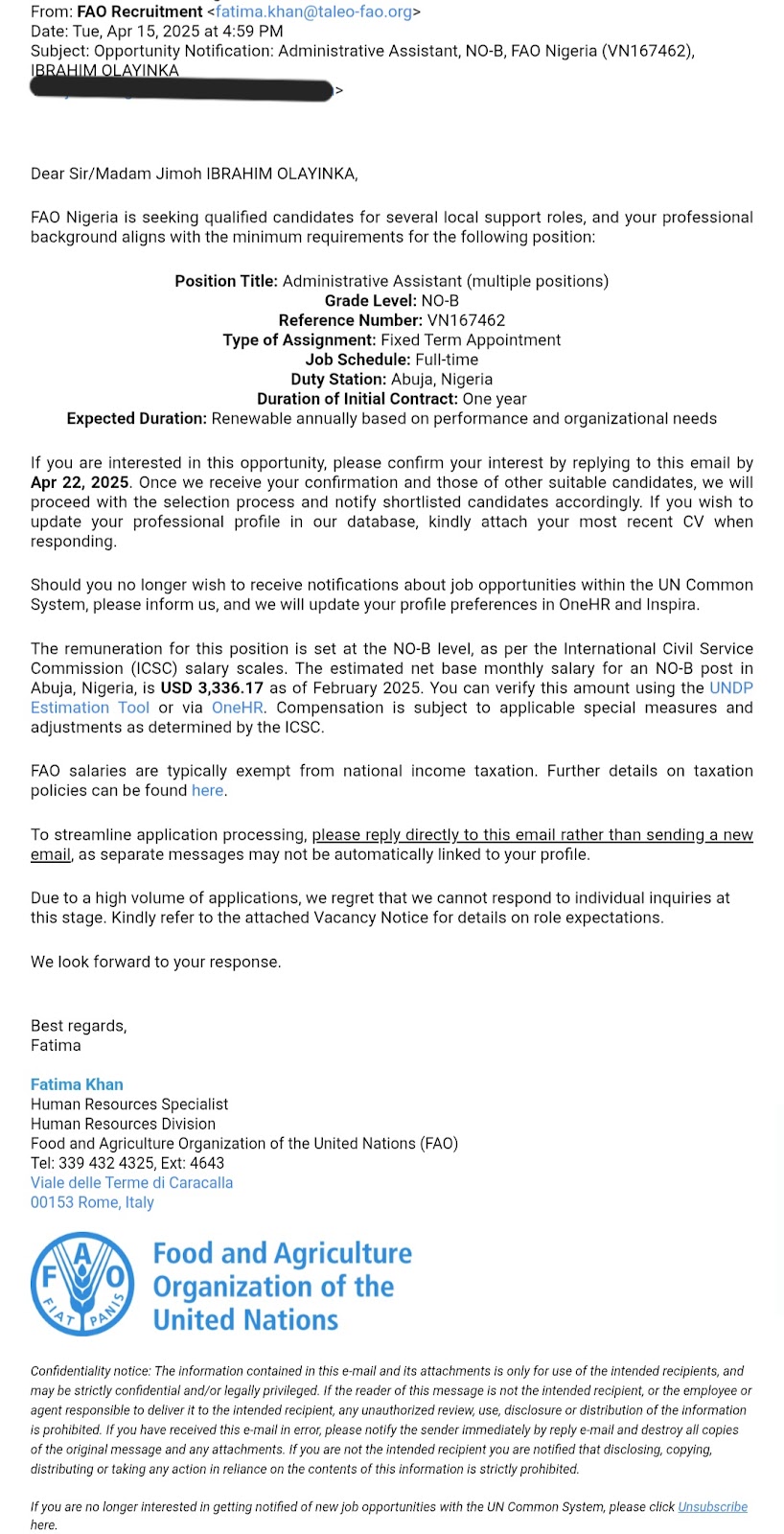

When Jimoh Ibrahim Olayinka received an email from someone claiming to represent the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, it appeared harmless. It was just a polite note inviting him to express interest in an open role. The position was Administrative Assistant at the FAO Nigeria office. The salary was over $3,000 per month. The sender promised further steps if he responded with confirmation and his most recent CV.

Jimoh replied.

Days later, he received what looked like an official offer of employment: a letter of appointment, a list of onboarding requirements, and instructions to complete two mandatory trainings, one of which was “QREDIV®,” with a professional-sounding name designed to appear legitimate. It required a payment of $99. The fee, he was told, would be reimbursed after probation.

For Monica Agbane, the experience was even more jarring. She did not recall applying, but the email seemed tailored, bearing her name, referencing legitimate UN training, and offering a prestigious post within FAO Nigeria. Already registered on the UN careers portal, Monica assumed it was a delayed response to a past application.

The language was polished, the documents convincing, and the domains like taleo-fao.org deceptively professional. Believing this to be the career break she had been waiting for, she paid for the required certificate and began preparing to relocate. It was not until she stumbled on a thread on X (Twitter), she realised that dozens of people had received the same offer, word-for-word, same role, same letter, same process.

“You’ll think so hard about when you applied,” @jhaarmmyy shared on a thread he wrote about the scam on X (formerly Twitter). “But you won’t remember. That’s because you didn’t.”

Jimoh, Monica, and many others had become targets in a sophisticated and deeply personal scam, one that exploited not just their professional hopes but the prestige and legitimacy of the United Nations system.

In this report, FactCheckAfrica goes beyond headlines and disclaimers. Drawing from firsthand accounts, digital forensics, open-source investigation, and official warnings, including from FAO Nigeria. We piece together how this scheme worked, who it targeted, and why it was so convincing.

We also ask the hardest question of all: why are scams like this still working, and what does it say about the systems, both technological and institutional, that failed to stop it?

The Scam Breakdown

In 2023, reports of job scams continued to rank as the second most dangerous type of scam worldwide, with investment scams being number one. These reports surged by 54.2% compared to the previous year.

In 2025, the FAO recruitment scam circulating in Nigeria was not as crude or chaotic as typical email scams; it was polished. Unlike the typical spam email from a foreign prince, this one began with restraint, precision, and hope. It looked professional, used the right lingo, and mimicked the tedious formalities of international hiring.

For many victims, the first contact came through an unsolicited email offering a job with FAO Nigeria. The position sounded credible: an Administrative Assistant role in Abuja with a net monthly salary of $3,336.17. It cited a familiar UN job grade (NO-B) and a reference number (VN167462). The sender, “Fatima Khan,” claimed to be an HR specialist in Rome, using the domain @taleo-fao.org, a calculated twist on Taleo, an actual recruitment platform used by many UN agencies.

After confirming interest, victims were sent onboarding documents and told to complete mandatory pre-employment training. One was BSAFE, a real, free UN security training. The second was QREDIV® or GENDIQ, entirely fictitious certifications tied to emotional intelligence and diversity compliance. Victims were asked to pay roughly $99 for the certificate through obscure third-party sites, reassured they’d be reimbursed after probation. The mix of real and fake elements made it easy to overlook the fraud.

The emails were carefully crafted to mirror official UN correspondence; cold, bureaucratic, and urgent. Deadlines were tight: “If we do not receive your signed appointment letter and certificates by May 22, the offer will expire.” Recipients were told not to follow up, echoing real HR protocol, which helped isolate them further. The tone instilled both urgency and prestige, making victims feel lucky, yet replaceable. Once someone had submitted their CV or completed one step, they were far more likely to go through with the payment, trapped by the sunk cost fallacy.

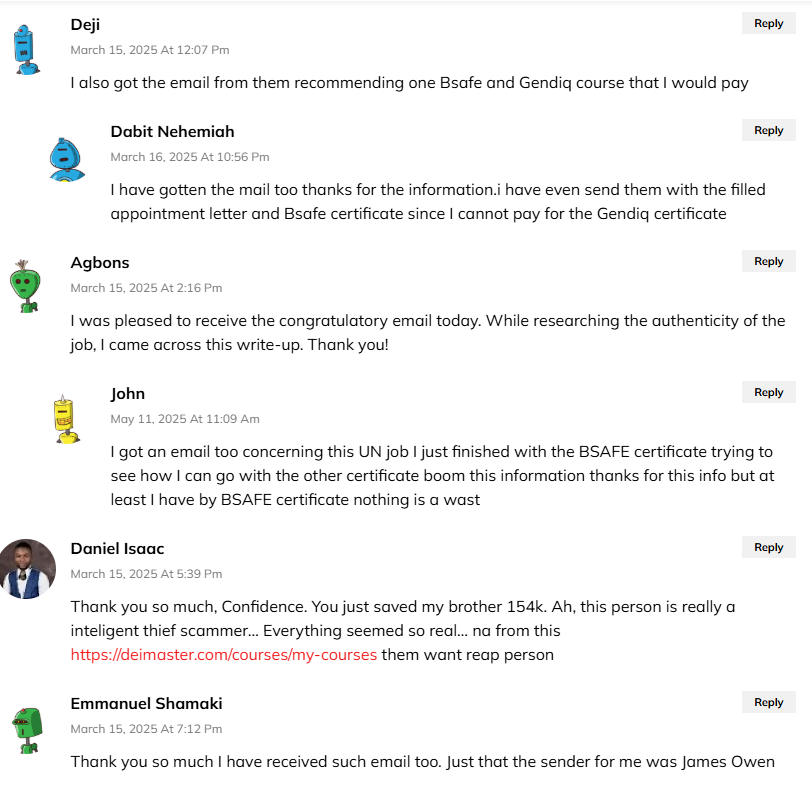

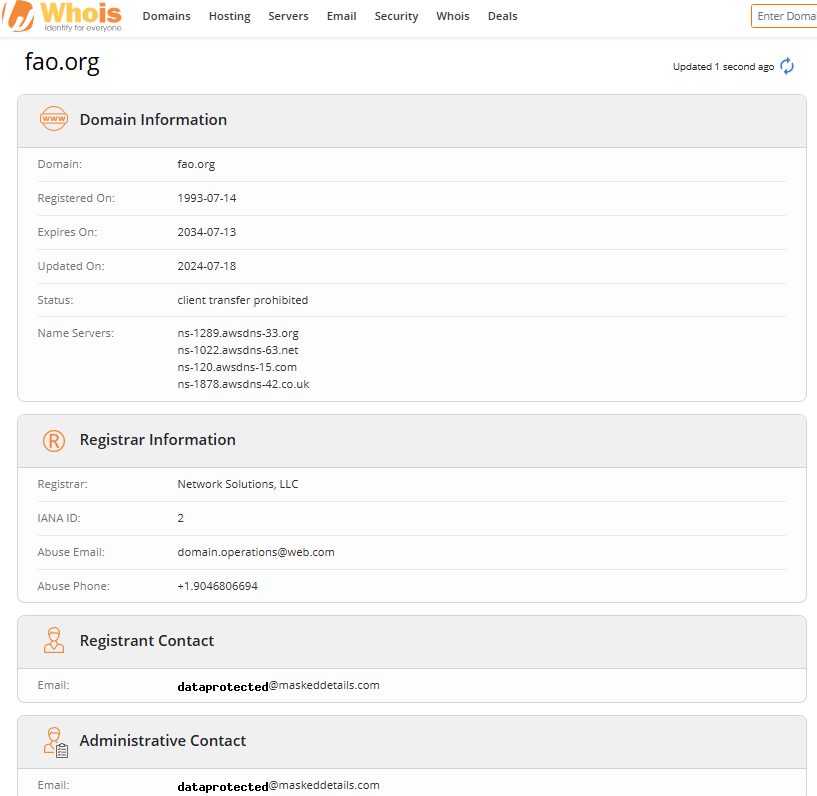

Screenshot of comments on the West Africa Weekly’s report

This was no one-off scam. On LinkedIn, Facebook, and X (formerly Twitter), dozens of Nigerians began comparing notes, same offer letter, same HR contact, same certificate link. The scammers used sophisticated templates with only the names swapped. The fake domain (@taleo-fao.org) and others like it were tied to non-UN servers and registered under privacy shields. Names like “Fatima Khan”, “Emilio Fernandez”, “Alvin Knox”, and “Elliot Murray,” which do not exist in FAO directories, appeared repeatedly across multiple scams, as noted in West Africa Weekly’s report.

But how could such a convincing scam bypass so many checks? FactCheckAfrica decided to conduct a closer technical investigation to reveal the cracks.

Verification

To verify the legitimacy of the so-called FAO job offers, FactCheckAfrica took a close inspection of the communication materials, links, and supposed onboarding requirements, which reveal multiple red flags and clear evidence of fraud.

- The Fake Domain: “taleo-fao.org”

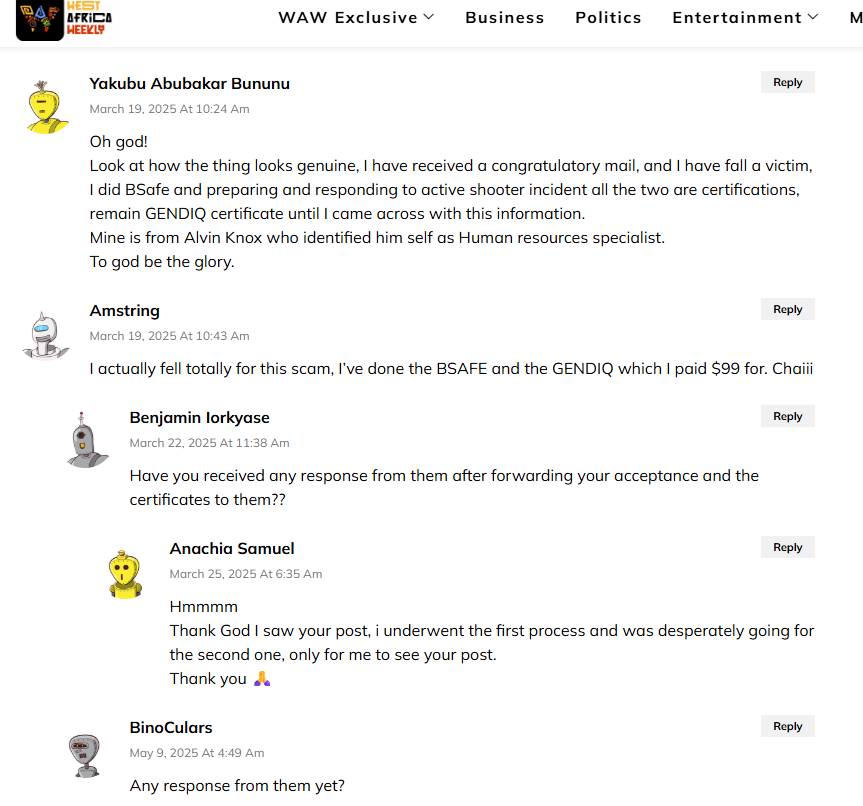

The scammers operated under a misleading web domain: taleo-fao.org, an obvious attempt to mimic Taleo, Oracle’s recruitment platform widely used by international organizations. However, a deeper look at the domain registration details confirms it is in no way affiliated with the real FAO. Verifying the domain via Whois lookup, an open-source tool used to find public information about a domain name, including who owns it, their contact details, and the domain’s registration and expiration dates.

FactcheckAfrica found that the taleo-fao.org domain was registered on February 25, 2025, and it expires on February 25, 2026. The domain was registered by Porkbun LLC (a common low-cost domain registrar). The taleo-fao.org leads to the official fao.org website, because the domain registrar platform, Porkbun LLC, on which taleo-fao.org was hosted, offered URL forwarding.

URL Forwarding is a simple way to redirect traffic from your domain to somewhere else, whether that’s another existing website or even internally on your original domain. With this option, whenever users click on the domain, it ultimately loads to the original FAO domain, thereby masking the scam.

Screenshot of the Whois Lookup for taleo-fao.org || FCA

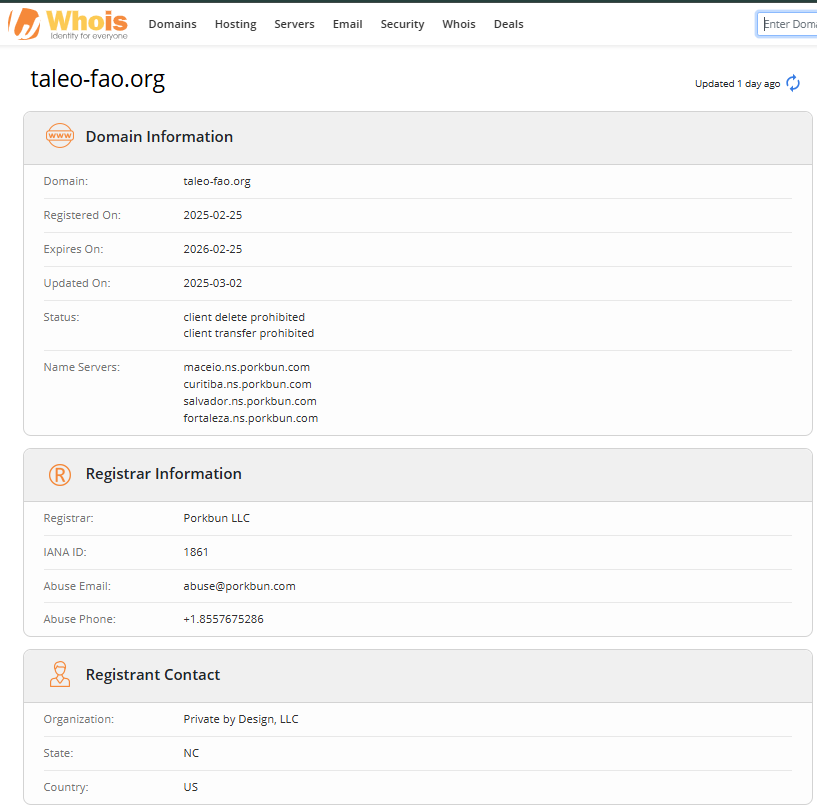

The FAO’s official careers portal is www.fao.org/employment and only uses the domain “@fao.org” for all email correspondence. We checked the FAO domain using the Whois lookup. The domain was registered on 1993-07-14 and expires on 2034-07-13, showing a longer span befitting an international organisation of FAO status compared to the taleo-fao.org with just a one-year span.

Screenshot of the Whois Lookup for Fao.org || FCA

The use of “taleo-fao.org” is a blatant violation of FAO’s communication policy and a hallmark of a phishing operation designed to appear authentic to unsuspecting users.

- The Phantom Certification: QREDIV®

One of the most striking elements of the scam is the requirement for a so-called QREDIV® certificate, which victims were told was essential for diversity and inclusion compliance before employment could be finalized. However, FactCheckAfrica’s review of FAO’s internal training databases, HR policy documents, and onboarding manuals found no mention of QREDIV® whatsoever. It is not an officially sanctioned UN training, nor does it exist in any credible international HR or DEI framework. This certification served one purpose: extracting money from job seekers under the pretence of legitimacy.

- Communication Irregularities

A number of technical inconsistencies in the scam emails further highlight their illegitimacy:

- No FAO Domain: None of the emails came from “@fao.org.” Instead, addresses from suspect domains or personal email providers were used.

- Untraceable Contact Information: Phone numbers were either listed without international dialling codes or with formatting errors inconsistent with United Nations standards.

- Generic and Vague Language: The offer letters lacked specific job descriptions, reporting structures, and standard UN job classification codes—details that would typically be present in authentic FAO recruitment.

- Official FAO Warning

On May 19, 2024, FAO Nigeria issued an official public disclaimer stating:

“FAO Nigeria did NOT issue these vacancies as contained in the said advertisement. The origin and the email address provided in the body of the document are NOT known nor connected to FAO in any way.” – FAO Nigeria Employment Disclaimer

The organization stated to the public that its recruitment process is solely through official channels and that no fees are required at any stage. Furthermore, onboarding does not necessitate payments for training or certifications. The organization maintains a strong stance against fraud and urges anyone who suspects fraudulent activity to report it to [email protected] or their local police.

The Victim Narratives: Personal Accounts of Deception

The scale and emotional weight of this scam are painfully shown in the dozens of firsthand accounts shared online. It has exploited the hopes of job seekers across Africa, many of whom believed they were on the verge of a prestigious international career with the United Nations or a related global agency.

The experiences of victims like Jimoh and Monica reflect a disturbing trend of people being preyed upon during their job search. For Jimoh, his initial excitement soon turned to frustration and regret as the process revealed itself to be a fraudulent scheme. Having spent time preparing his documents, he was taken aback by the unexpected request for payment, which triggered his doubts. The sense of being scammed compounded the emotional distress of believing in a bright future only to have it snatched away.

Monica, meanwhile, shared her experience of receiving the offer email, initially believing that she had secured her dream job. However, after being asked for personal details and payment for certification, she realized too late that the process was a scam. Her candid post on LinkedIn and the outpouring of support from other victims shed light on just how prevalent these scams are in the job market, and how the emotional cost of such deception runs deep.

What is clear from the accounts of these victims is the emotional manipulation at play. Victims are led to believe they are at the threshold of their ideal careers, only to find themselves victims of exploitation and fraud. The scam not only costs them financially but also leaves them with a sense of betrayal, damaging their trust in legitimate opportunities.

One victim, Daniel Isaac, summed up the deception bluntly: “You just saved my brother 154k. This person is really an intelligent thief… Everything seemed so real.” Others echoed similar disbelief. Mohammed Hassan wrote, “I am still struggling to sell my plot of land just to pay for that shit… but thank you.” Several, like Maurice, expressed quiet relief: “Thank you, you saved my small money.”

Many described how far they had gone in the application process, completing the BSAFE training, signing appointment letters, and planning to pay for additional certificates like GENDIQ or QREDIV. John shared: “I just finished with the BSAFE certificate, trying to see how I can go with the other certificate, boom, this information. Thanks!” Others, like Amstring, weren’t as lucky: “I actually fell totally for this scam… I paid $99 for the GENDIQ.”

Some victims like Chuks only narrowly escaped: “I had thought my details came from an assignment we did with UNIDO some years ago… was just arranging the $99 before I ran into this post. These guys almost got me.” The deception was so deep, it even manipulated legitimate UN training platforms, leading Seye Adeniran to ask in confusion: “I keep wondering why the BSAFE certificate came from the FAO-UN portal if this was fake. Is the scammer that skillful?”

What emerges from these testimonials is not just financial loss, but a sense of betrayal and stolen dignity. Adeyemi Toheeb lamented: “I have done BSAFE and also paid 150k for the GENDIQ… I paid to Justice Group account using GTBank. I’m totally confused.”

Why Job Scams Still Work—and What We Must Do to Stop Them

According to the Nigeria Labour Force Survey Q3 2023 report by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Nigeria witnessed a significant increase in its unemployment rate, rising from 4.2% in Q2 2023 to 5.0% in Q3 2023. The NBS also noted a decline in the labour force participation rate among the working-age population, dropping to 79.5% in Q3 2023, down from 80.4% in Q2 2023. In Nigeria, where the unemployment rate and economic hardship remain pressing issues, job seekers often navigate a landscape fraught with pitfalls. The promise of a lucrative job with a reputable company can blind individuals to the red flags of potential scams.

Scammers capitalize on this desperation by posing as representatives of well-known organizations or recruitment agencies, offering enticing job opportunities in exchange for upfront payments or personal information. In April 2023, a former Integrated Payroll and Personnel Information System desk officer at the Federal Character Commission, Haruna Kolo, admitted to collecting money from job seekers in exchange for employment. He also admitted to having received over N75m from desperate job seekers on the instructions of the Chairman of the FCC. The Nigerian Army (NA) also expressed dismay over the alarming rate of the spread of fake online recruitment information, particularly regarding the Nigerian Army Direct Short Service (DSS) Recruitment Portal for the year 2023.

Scams like this continue to work because they exploit systemic weaknesses, both technological and institutional, and prey on the emotional and financial vulnerability of job seekers. The sophistication of these scams, which blend real elements (such as actual UN training) with fabricated ones (like fake certifications and HR contacts), makes them difficult to detect. Institutional failures, such as delayed public warnings and a lack of centralized scam-reporting mechanisms, allow these fraudulent operations to spread widely before they are flagged. Technological loopholes, like the misuse of domain registration and URL forwarding, further enable scammers to create realistic imitations of trusted organizations. The reliance on email and digital correspondence in job recruitment, combined with job seekers’ limited access to verification tools, gives these scams continued leverage.

However, the persistence of such scams also highlights the need for increased public awareness and individual empowerment. Many victims, like Jimoh and Monica, were unaware of the proper channels to verify job offers, and only recognized the fraud after emotional or financial harm had been done. This underscores the importance of proactive education, vigilance, and transparency in both personal conduct and organizational practices. When job seekers are informed about verification methods, warning signs of fraud, and how to respond if targeted, they are better equipped to avoid deception. Institutions, in turn, must prioritize timely communication, strengthen digital security, and support public reporting systems. Only through a combined effort of awareness, institutional accountability, and individual empowerment can the cycle of these scams be broken.

Conclusion

With a 118% rise in job scams in 2023, and nearly half of job seekers struggling to avoid them, it’s clear this problem is growing rapidly. These scams often begin with attractive job offers, only to end in financial loss or identity theft as scammers request upfront payments or sensitive personal information. As job scams become more sophisticated, job seekers must remain cautious, verify offers, and report suspicious activity to help curb this alarming trend.

The FAO job scam is a reminder of the lengths to which scammers will go to exploit the hopes and aspirations of vulnerable individuals. The reality is that these fraudulent schemes will continue to evolve. But with greater awareness, a proactive approach to verification, and community vigilance, we can make it more difficult for scammers to succeed. Ultimately, it’s about creating an environment where job seekers feel empowered, educated, and supported in their search for legitimate opportunities.

If you suspect a job scam or have been targeted, report to the relevant authorities and flag the recruiter on job platforms, social media, and online communities to protect others from falling prey. Awareness is the first defence.