Fact-Check: Are Niger Delta Militants the First Terrorists in Nigeria?

BY: Oluwaseye Ogunsanya

Claim

An X user with the username, Sarki @Waspapping_ claimed that the first terrorists in Nigeria were the Niger Delta militants

Verdict

False. Niger Delta militants are not the first terrorists in Nigeria. Studies agree that Maitatsine (1980s) is the first terrorist organisation in Nigeria.

Full Text

An X user with the username, Sarki @Waspapping_ claimed that the first terrorists in Nigeria were the Niger Delta militants

The post which had no clear context has garnered 84 reposts, 98 quotes and over 700 likes.

Photo Credit: Screenshot of the claim/X

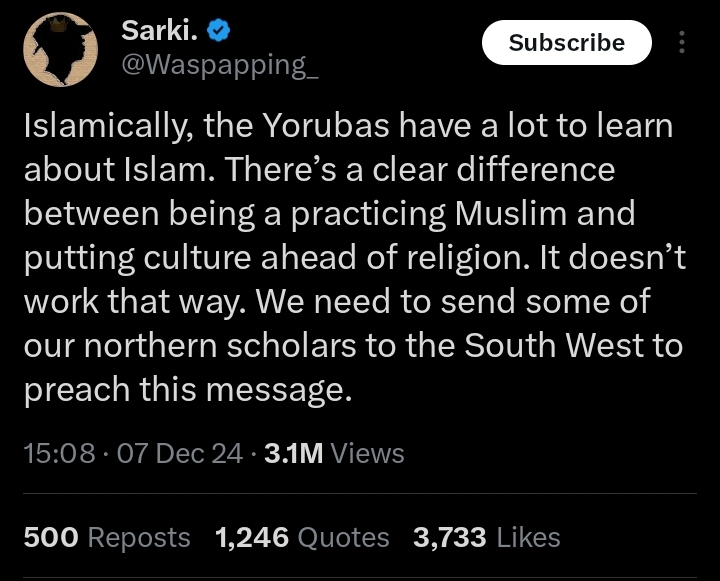

The user is known for advancing controversial views along ethnic and religious lines. He recently made an inflammatory remark suggesting that it was wrong for Yoruba Muslims to prioritize culture over Islamic principles.

“Islamically, the Yorubas have a lot to learn about Islam. There’s a clear difference between being a practicing Muslim and putting culture ahead of religion. It doesn’t work that way. We need to send some of our northern scholars to the South West to preach this message.” He posted.

Photo Credit: Screenshot of the remark/X

Verification

What is Terrorism?

There is no consensus over the definition of the term ‘terrorism’. According to an article titled ‘Historical Antecedents of Terrorism in Nigeria’, terrorism is a concept that can generate hot emotional exchanges because of differing perspectives and different understanding of its causes.

This view was corroborated by another article entitled ‘Growth and Fiscal Consequences of Terrorism in Nigeria’ which stated that “any meaningful discussion of the impacts of terrorism requires a clear perspective on the definition of the concept, especially in the light of the controversy about what should, and should not be classified as terrorism.” Therefore, we will be adopting the official and policy-relevant definitions of terrorism used by relevant international organisations especially that of the United Nations (UN) and the US Department of Defence.

While the United Nations defines it as “An anxiety-inspiring method of repeated violent action, employed by (semi-) clandestine individuals, group or state actors, for idiosyncratic, criminal or political reasons, whereby-in contrast to assassination, the direct targets of violence are not the main targets”. The US Department of Defence defines the concept as “the calculated use of unlawful violence or threat of unlawful violence to inculcate fear; intended to coerce or to intimidate Governments or Societies in the pursuit of goals that are generally political, religious, or ideological”.

Types of Terrorism

Terrorism remains one of the most significant security challenges worldwide, manifesting in various forms and with far-reaching consequences. According to (Uche, 2011) in Osewa (2019), terrorism can be classified into three primary types: state terrorism, domestic terrorism, and international or transnational terrorism. These categories provide a clearer understanding of the motives, scope, and operations of terrorist activities.

State terrorism refers to the use of violence and fear by governments to suppress opposition and maintain control. It is often targeted at dissenters to preserve the status quo and can range from repressive policies to outright violence. Historical examples include the repressive actions of the French monarchy during the French Revolution, the Nazi regime in Germany, Stalin’s government in Russia, and Samuel Doe’s administration in Liberia. In Nigeria, General Sani Abacha’s military regime is a notable example, characterized by human rights violations and the suppression of political opposition.

Domestic terrorism, on the other hand, occurs within a single country’s borders and is often perpetrated by groups or individuals rebelling against their government. Such acts are typically aimed at overthrowing the current order, seeking revenge, or creating chaos. Eku (2018) describes this form of terrorism as dissent terrorism, highlighting groups that act within their geographical limits to challenge the state. A prime example of this is Boko Haram in Nigeria, a group whose activities have devastated lives and property in its pursuit of an Islamic state.

International terrorism transcends national boundaries, involving acts carried out by individuals or groups with operations that span multiple countries. This form of terrorism often includes collaborations between nationals of different states and is characterized by its global impact. Al-Qaeda, known for its extensive cross-border operations, is a quintessential example. Similarly, cyber-terrorism falls into this category, as it targets systems and entities across nations, disrupting economies and governance structures.

Features of Terrorism

From a close study of terrorism, it has been identified that at least four traits are discernible as common features of terrorism (Uche, 2011), Joseph (2010) posits that they are:

- Objectives: Some of the objectives are to publicize the existence and cause of the group on a national or international basis, to intimidate and coerce the public into supporting their demands to undermine and discredit the act horrifies who oppose their cause, and to provoke repressive counter-measures in order to gain sympathy. To de-legitimize internal value, culture and destabilize internal security.

- Actors: State as well as non-state actors, including groups and individuals, are usually the perpetrators of terrorism.

- Targets: Both human beings and property can be targets of terrorism with special focus on targets that provide the widest publicity such as landmark buildings and high placed persons.

- Methods: Perpetrators of terrorism use violence including bombing, kidnapping, killings and hostage-taking in spreading fear among the targeted population.

Terrorism in Nigeria

Conflict is not a new phenomenon in Nigeria. Spanning from the Civil War to the Maitatsine movement of the 1980s and the Niger Delta militants, insecurity and dissent issues have often faced the Nigerian polity.

In a research titled, ‘History And Dynamics Of Terrorism In Nigeria: Socio-Political Dimension’ the author attempted to provide a comprehensive historical and political analysis of terrorism in Nigeria by tracing its roots from pre-colonial times through the colonial, post-independence, and contemporary eras.

According to him, terrorism in Nigeria is not a recent phenomenon, its rise and evolution have been marked by distinct historical, socio-political, and economic dynamics.

During the pre-colonial era, secret societies such as the Ogboni and Ekpe engaged in activities resembling modern-day terrorism, such as intimidation and violence. The colonial period amplified this trend, with British administrators using acts of terror to suppress resistance, enforce imperial policies, and exploit resources. For instance, the Oke-Ogun uprising of 1921 and the Aba Women’s protest of 1929 were brutally quashed, leaving thousands dead.

Post-independence, political and ethnic conflicts became prominent drivers of terrorism. The first and second republics witnessed communal violence, electoral crises, and politically motivated assassinations. Events like the Tiv riots and the Western Region crisis of 1965 showcased the deep divisions within the nascent state. The military era further entrenched terrorism, with state-sponsored acts such as the parcel bomb assassination of journalist Dele Giwa in 1986 during General Babangida’s regime.

The return to democracy in 1999 brought hope but also new challenges. Ethnic militias such as the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB) and the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) emerged, voicing grievances over resource control and political marginalization. Meanwhile, Boko Haram introduced a new dimension of religious extremism, employing suicide bombings and mass attacks that destabilized the nation.

Chinwokwu identifies key motivations for terrorism in Nigeria, including political agitation, economic deprivation, religious extremism, and regional demands for self-determination. The government’s response has included military crackdowns, dialogue attempts, and legislative measures such as the anti-terrorism bill. However, systemic issues like corruption, poor governance, and lack of political will continue to hinder progress.

Another account by Ikedinma Hope, in a research article entitled ‘Historical Antecedents of Terrorism in Nigeria‘ narrated that Nigeria faced significant challenges to its security and socio-political stability when the nation transitioned to democracy in 1999. This was demonstrated by diverse conflicts, upheavals and anti-government agitations

He added that the opening of the democratic space in 1999 gave rise to various militia groups, many of which have used religion, ethnicity, or other special interests as rallying points. Groups such as the Odua People’s Congress (OPC), Egbesu, the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB), Arewa People’s Congress (APC), the Bakasi Boys, Igbo Youth Congress (IYC), Igbo People’s Congress (PC), Niger Delta Volunteer Force (NDVF), Niger Delta Resistant Movement (NORM), Movement for the Survival of the Izon Nationality of the Niger Delta (MOSIEND), the Nigerian or Yobe Taliban, Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) and the more famous Boko Haram emerged during this period. According to Yahaya (2013), “These groups emerged largely due to the failure of governance, a complacent security regime, and the absence of a strong culture that enables citizens to hold their rulers accountable,”

While their goals vary, their activities have consistently disrupted peace and stability. The Niger Delta militants, for example, are motivated by deep feelings of economic injustice and political marginalization. Their struggle is rooted in the need for resource control and restructuring of the federation. Similarly, the OPC’s activities reflect the Yorubas’ grievances over perceived political exclusion, particularly following the annulment of the June 12, 1993, presidential election claimed to be won by Chief M.K.O. Abiola.

While some groups, such as Boko Haram, employ religious extremism and indiscriminate violence, others focus on collective grievances with more selective methods. The Niger Delta militants, for instance, mobilize grassroots support using traditional symbols and cultural solidarity. “The basis of their struggle is self-determination, not religious bigotry,” Yahaya explains.

Were The Niger Delta Militants the First Terrorists in Nigeria?

No, various studies have identified a group known as Maitatsine as the first terrorist group in post independence Nigeria. According to Agbiboa and Maiangwa in ‘Nigeria United in Grief; Divided in Response: Religious Terrorism, Boko Haram, and the Dynamics of State Response’, The Maitatsine uprisings in post-independence Northern Nigeria marked the first organized religious militancy in the region. Led by Muhammadu Marwa, a Cameroonian preacher opposed to modernity and Western influence, the movement attracted Kano’s urban poor with promises of salvation. Violent clashes with state security forces in 1980 resulted in over 4,000 deaths and subsequent extrajudicial killings. The unrest continued through the 1980s, signaling the rise of religious extremism in Nigeria and demonstrating how ideology can connect radical groups across borders.

This above account was similar to that of Egbefo and Shedrack which went further to quote Danjibo (op. cit.) who stated that “similar to Maitatsine (if not the same), the leader of the Boko Haram movement, Yusuf was a secondary school drop out who went to Chad and Niger Republic to study the Quran. While in the two countries, he developed radical views that were abhorrent to Westernisation and modernisation. Like the late Maitatsine, Yusuf got back to Nigeria, settled in Maiduguri and established a sectarian group in 2001 known as the Yusufiyya, named after him. The sect was able to attract more than 280,000 members across Northern Nigeria as well as in Chad and Niger Republic.” Yusuf began his radical and provocative preaching against other Islamic scholars such as Jafar Adam, and Abbas Yahaya Jingir and against established political institutions.

Enter Boko Haram

Literature abounds on the Boko Haram sect, as various researchers and authors have extensively studied different dimensions of the terrorist organisation and its effects on Nigeria and Nigerians. What distinguishes Boko Haram from other groups is their motivations, mission and demand. The Boko Haram insurgency has raised significant concerns among the Nigerian government and international community more than any other groups.

As aptly captured by Ikedinma (2017) “Boko Haram groups are different from those of other groups and can easily lead to total disintegration of any political system. From the outset, the mission of Boko Haram is to stifle Western culture and democracy. In order to actualize their objective, Boko Haram has committed acts of terrorism. They intended to advance a religious and political cause by aiming to intimidate the Nigerian government to create Sharia law and intimidate the Christian public. Acts committed by this group have not been advocacy, protest, dissent or industrial action that is not intended to cause serious harm that is physical to a person. Boko Haram members are not freedom fighters or religious fanatics. Boko Haram meets the entire requirements for it to be defined and proscribed as a terrorist organization. Usually, the adoption of Sharia law and the creation of an Islamic government are prominent motivations for religious terrorism within the current climate.”

According to Agbiboa, The nomenclature ‘Boko Haram’ is derived from a combination of the Hausa word ‘boko’ (book) and the Arabic word ‘haram’ (unlawful). Combined, Boko Haram means ‘Western education is unlawful.’ Boko Haram was derived as a nickname given to the movement by outsiders by truncating a slogan repeated by the late Mohammed Yusuf on video discs, prohibiting not just the colonial European format of literacy but any collaboration with the neo-colonial state (Manfredi, 2014: 2). In any case, Boko Haram has even rejected the designation, ‘Western education is unlawful’, and instead, prefers the slogan, ‘Western culture is forbidden.’ As a senior member of the group explained, ‘culture is broader, it includes education but not determined by Western education’ (cited in Onuoha, 2012: 136). In northern Nigeria a distinction is often drawn between makarantan boko (schools providing ‘Western’ education) and makarantan addini (school for religious instruction) or makarantan allo (school of the slate understood to be Koranic schools) (Danjibo, 2009: 8). Across northern Nigeria, makarantan boko continues to be linked to attempts by evangelical Christians to convert Muslims who fear the southern economic and political domination. Isa (2010: 322) argues that Boko Haram implies a ‘sense of rejection’ and ‘resistance to the imposition of Western education and its system of colonial social organisation, which replaced and degraded the earlier Islamic order of the jihadist state [the Sokoto Caliphate]’.

Since July 2009, Boko Haram, the ‘Nigerian Taliban from northeastern Nigeria, has stepped up its violence against the Nigerian state and its citizens, unleashing a systematic campaign of bombings, kidnappings and drive-by shootings on diverse government and civilian targets. In May 2013, President Goodluck Jonathan declared a state of emergency in the worst hit northeastern states of Borno, Adamawa and Yobe. But such emergency measures have failed emphatically and woefully to turn the tide of the insurgency; instead, they have strengthened the group’s resolve to impose its will on Africa’s most populous country. Following an intensified state offensive against Boko Haram, thousands of Nigerians are fleeing into neighbouring countries fearing retaliatory attacks and general insecurity.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) recently announced that up to 10,000 Nigerians have fled to Niger’s Diffa region. Cameroon is currently hosting some 44,000 Nigerian refugees; another 2,700 have fled to Chad. The vast majority of those fleeing are women and children. Meanwhile, some 650,000 people remain internally displaced in northeastern Nigeria due not only to Boko Haram’s acts of domestic terrorism but also the counter-terrorism and indiscriminate killings of the state-led Joint Military Task Force (JTF) (Baiyewu 2014). In an October 2014 report, the Human Rights Watch noted that Boko Haram kidnapped over 592 persons (mostly girls, boys and women) in 2014. The group has since broken into splinter groups.

Niger Delta Militancy

The Niger Delta region of Nigeria has experienced persistent agitation against environmental degradation and inadequate infrastructure, particularly from Ijaw youths, since the 1990s. This intensified with the Ijaw Youth Council’s Kaiama Declaration in December 1998, which demanded that oil companies suspend operations due to the adverse effects of oil exploration, including land and food shortages and severe pollution.

Despite the region’s significant contribution to Nigeria’s economy, providing 95% of foreign exchange and government revenue, local communities feel neglected and marginalized. The dissatisfaction led to the formation of militant groups like the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) led by Henry Okah, the Niger Delta Peoples Volunteer Force (NDPVP) led by Asari Dokubo and the Niger Delta Vigilante led by Ateke Tom. There are also other smaller armed militia groups such as the Tombolo Boys (TTB), Joint Revolutionary Council (JRC), Matyrs Brigade (MB) and Icelanders Coalition for Military Action (ICMA), who engaged in violent activities, including kidnappings and vandalism, significantly impacting oil production and revenue from 2006 to 2009.

The Nigerian government’s initial military response to the militants proved ineffective and resulted in substantial loss of life. In 2008, President Yar’adua established the Niger Delta Technical Committee, which recommended an amnesty program. Implemented in June 2009, the amnesty allowed over 20,000 militants to surrender their weapons in exchange for monthly stipends and vocational training. While the program aimed to restore peace and facilitate oil operations, studies suggest that the root cause of militancy—underdevelopment in the region—remains unaddressed.

Other Groups

It is important to note that the Nigerian government has proscribed other groups such as the Islamic Movement in Nigeria (Shiites’ movement) and the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) as terrorist organisations in recent times. However, in 2023, a state high court sitting in Enugu nullified the 2017 proscription of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) as a terrorist organisation.

Conclusion

Based on our indepth research and subsequent findings, we can undoubtedly conclude that Niger Delta militants are not the first terrorists in Nigeria as stated by the claimant. The Maitatsine were seen as the first group to carry out terrorist activities in Nigeria.